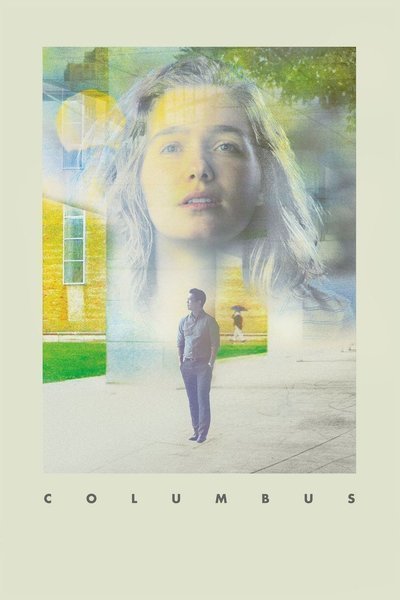

Columbus

100 min | DCP

The buildings rise up out of the grass and trees like relics of a mysterious, more sophisticated civilization. They are abstract, startling, sometimes anti-gravitational. They are not monuments. They were built for utilitarian purposes: banks, offices, a church, a library, a hospital. These geometric modernist buildings pepper the landscape of the “Midwest Mecca of Architecture,” Columbus, Indiana, and were designed by some of the most innovative architects of the 20th century: It’s no wonder people travel there from all over to take architecture tours. Columbus’s architecture is the canvas for “Columbus,” the stunning directorial debut of Kogonada (mainly known up until now as a video essayist). What Kogonada has done with “Columbus” (along with cinematographer Elisha Christian) is to blend the background into the foreground and vice versa, so that you see things through the eyes of the two architecture-obsessed main characters. Watching the film is almost like feeling the muscles in your eyes shift, as you look up from reading a book to stare out at the ocean. From the very first shot, it’s clear that the buildings will be essential. They are a part of the lives unfolding in their shadows. Sometimes it almost seems like they are listening.

There is a story in “Columbus.” What is remarkable is how intense it is, given the stillness and quiet of Kogonada’s style, and the focus with which he films the buildings.

A Korean-born man named Jin (John Cho) travels to Columbus to care for his father, who is in the hospital following a catastrophic collapse. Accompanying him is an old friend (and possibly onetime lover), who was also his father’s star pupil, played by Parker Posey. Jin has a distant relationship with his father. He can’t connect with the worry and sadness his friend is feeling. On a separate track initially, we meet Casey (Haley Lu Richardson), working as a page at the Cleo Rogers Memorial Library (one of the most important interiors in the film). Casey has graduated from high school but has put off going to college perhaps indefinitely because her mother is a former meth addict. (“Meth is really big here,” says Casey. “Meth and modernism.”) She fears what will happen to her mother without her. Casey and a coworker (Rory Culkin) have interesting discussions, sitting amidst the towering stacks, their conversations a blend of tentative flirting, kindness and gentle debate. One day, Jin bums a cigarette from Casey. They strike up a conversation.

Over the course of “Columbus,” Casey, obsessed with architecture, takes Jin around, showing him her favorite buildings (she has a list). Jin is significantly older than Casey, but he treats her as a peer. There is instantly an intimacy between them, perhaps because both are so exhausted by their life circumstances. Their dynamic is fascinating. There’s an irritable quality to some of it, as though neither one of them wants to let the other “get away with” just skating off the surface of things. When Casey rattles off facts about the famous glass bank designed by Eero Saarinen, Jin gets bored. He pushes her to go deeper: What does the building make you feel? There were only a couple of moments when the script was a little on the nose. But even in those moments the characters were wandering through such interesting spaces that there was always plenty to look at.

Kogonada places their human figures against striking man-made backdrops with extreme care. He chooses his angles meticulously. There isn’t an uninteresting shot in the whole thing. Shots repeat. Alleyways, sculptures, doorways, glass walls, the clocktower with the asymmetrical clockface, the church with the asymmetrical cross ... we go back to them again and again, Kogonada giving us time to contemplate them, to sink into them. There’s so much sadness in the film, it seeps into the air. Kogonada allows space for it, interspersing the conversations between Jin and Casey, or Casey and her mother, with long still shots of the library’s striking ceiling, of the glass bank gleaming at night, of the glass walkway hovering over a river, of the two brick monoliths floating in the air, almost, but not quite, touching. It’s a profound approach. The depth of emotion the film stirred up surprised me. I got so involved in these two people’s lives. I cared about them. I liked eavesdropping on their conversations.

When I first moved to New York, every time I caught a glimpse of the Chrysler Building’s whimsical jewel-like crown, my breath would catch in my throat. Eventually, over time, I got used to it as part of my everyday world. But there are moments, usually at dusk, when suddenly it’s like I see it for the first time, and I stare upward, taking a moment to appreciate that architect William Van Alen thought that building up, that he saw something that beautiful in his mind and that he knew what it would add to the skyline: something so tall, and yet also so delicate. I try to remind myself: Make sure to look at the Chrysler Building on occasion. Make sure to appreciate it. “Columbus” is a movie about the experience of looking, the interior space that opens up when you devote yourself to looking at something, receptive to the messages it might have for you. Movies (the best ones anyway) are the same way. Looking at something in a concentrated way requires a mind-shift. Sometimes it takes time for the work to even reach you, since there’s so much mental ballast in the way. The best directors point to things, saying, in essence: “Look.” I haven’t been able to get “Columbus” out of my mind.