Ghost World

There's a small tomb in Southwark Cathedral that I like to visit when I am in London. It contains the bones of a teenage girl who died three centuries ago. I know the inscription by heart:

This world to her

Was but a tragic play.

She came, saw, dislik'd,

And passed away.

I thought of those words while I was watching "Ghost World," the story of an 18-year-old girl from Los Angeles who drifts forlorn through her loneliness, cheering herself up with an ironic running commentary. The girl is named Enid, she has just graduated from high school, and she has no plans for college, marriage, a career or even next week. She's stuck in a world of stupid, shallow phonies, and she makes her personal style into a rebuke.

Unfortunately, Enid is so smart, so advanced, and so ironically doubled back upon herself, that most of the people she meets don't get the message. She is second-level satire in a one-level world, and so instead of realizing, for example, that she is mocking the 1970s punk look, stupid video store clerks merely think she's 25 years out of style.

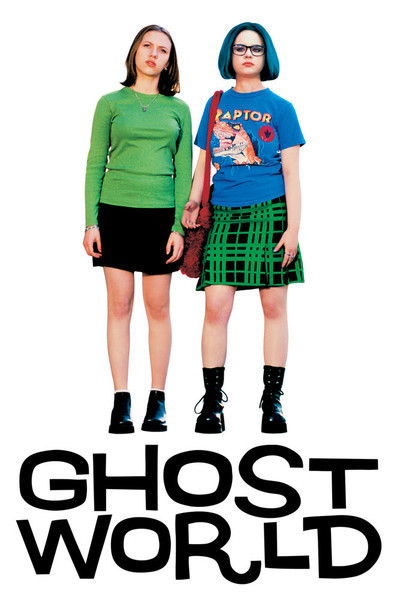

Enid is played by Thora Birch, from "American Beauty," and in a sense this character is a continuation of that one--she certainly looks at her father the same way, with disbelief and muted horror. Her running-mate is Rebecca (Scarlett Johansson). There's a couple like this in every high school: The smart outsider girls who are best friends for the purpose of standing back to back and fighting off the world. At high school graduation, they listen to a speech from a classmate in a wheelchair, and Enid whispers, "I liked her so much better when she was an alcoholic and drug addict. She gets in one stupid car crash and suddenly she's Little Miss Perfect." But now Rebecca is showing alarming signs of wanting to get on with her life, and Enid is abandoned to her world of thrift shops, strip malls, video stores and 1950s retro diners. One day, in idle mischief, she answers a personal ad in a local paper, and draws into her net a pathetic loner named Seymour (Steve Buscemi). At first she strings him along. Then, unexpectedly, she starts to like him--this collector who lives hermetically sealed in a world of precious 78 rpm records and old advertising art.

By day, Seymour is an insignificant fried chicken executive. By night, he catalogs his records and wonders how to meet a woman. Why does Enid like him? "He's the exact opposite of all the things I hate." Why does he like her? Don't get ahead of the story. "Ghost World" isn't a formula romance where opposites attract and march toward the happy ending.

Seymour and Enid are too similar to fall in love; they both specialize in complex personal lifestyles that send messages no one is receiving. Enid even offers to try to fix up Seymour, but he sees himself as a bad candidate for a woman: "I don't want to meet someone who shares my interests. I hate my interests." Seymour resembles someone I know, and that person is Terry Zwigoff, who directed this movie. It's his first fiction film. Zwigoff earlier made two documentaries, the masterpiece "Crumb" (1995), about the comic artist R. Crumb, and "Louie Bluie," about the old-timey Chicago string band Martin, Bogan and the Armstrongs. He looks a little like Buscemi, and acts like a Buscemi character: worn down, dubious, ironic, resigned. Zwigoff was plagued by agonizing back pain all during the period when he was making "Crumb," and slept with a gun under his pillow, he told me, in case he had to end his misery in the middle of the night. When Crumb didn't want to cooperate with the documentary, Zwigoff threatened to shoot himself. Crumb does not often meet his match, but did with Zwigoff.

Both Zwigoff and his character Seymour collect old records that are far from the mainstream. Both are morose and yet have a bracing black humor that sees them through. Seymour and Enid connect because they are kindred spirits, and it's hard to find someone like that when you've cut yourself off from mankind.

The movie is based on an underground comic book by Daniel Clowes, who co-wrote the screenplay with Zwigoff. It listens carefully to how people talk. Illeana Douglas, for example, has a perfectly observed role as the art teacher of Enid's summer make-up class, who has fallen for political correctness hook, line and sinker, and praises art not for what it looks like but for what it "represents." There are also some nice moments from Teri Garr, who plays the take-charge girlfriend of Enid's father (Bob Balaban).

One scene I especially like involves a party of Seymour's fellow record collectors. They meet to exchange arcane information, and their conversations are like encryptions of the way most people talk. This event must seem strange to Enid, but see how she handles it. It's Seymour's oddness, his tactless honesty, his unapologetic aloneness, that Enid responds to. He works like the homeopathic remedy for angst: His loneliness drives out her own.

I wanted to hug this movie. It takes such a risky journey and never steps wrong. It creates specific, original, believable, lovable characters, and meanders with them through their inconsolable days, never losing its sense of humor. The Buscemi role is one he's been pointing toward during his entire career; it's like the flip side of his alcoholic barfly in "Trees Lounge," who also becomes entangled with a younger girl, not so fortunately.

The movie sidesteps the happy ending Hollywood executives think lobotomized audiences need as an all-clear to leave the theater. Clowes and Zwigoff find an ending that is more poetic, more true to the tradition of the classic short story, in which a minor character finds closure that symbolizes the next step for everyone. "Ghost World" is smart enough to know that Enid and Seymour can't solve their lives in a week or two. But their meeting has blasted them out of lethargy, and now movement is possible. Who says that isn't a happy ending?