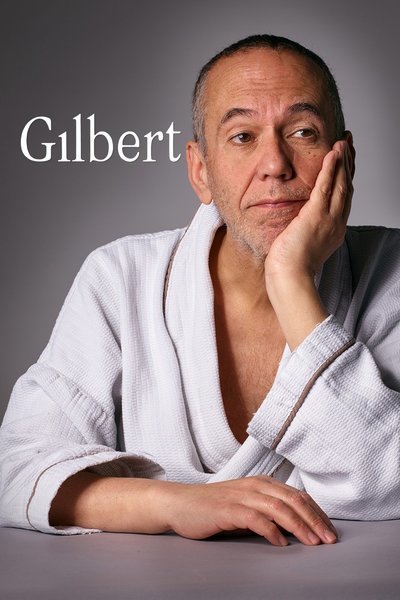

Gilbert

Courtesy of The Hollywood Reporter

Neil Berkeley's doc 'Gilbert' offers a surprising portrait of polarizing comedian Gilbert Gottfried.

In his two very fine previous documentaries, Neil Berkeley has focused on cult artists (painter Wayne White, TV creator Dan Harmon) who typically work behind the scenes. With Gilbert, a portrait of polarizing comedian Gilbert Gottfried, he looks at the surprisingly tender real human behind the grating personality America has known for over three decades. A laugh-packed and unexpectedly moving picture, it is now moving from a warmly received fest run to art houses; it should do even better once it hits video.

The doc’s big revelation comes early, as the audience realizes just how quiet and loving this professionally irritating man is with friends and family. Caught at home with wife Dara Kravitz and in cute moments with his two young kids, the performer admits “it doesn’t seem real to me” that he found someone who could see beyond his quirks.

Those quirks make for good movie moments, of course. Known among fellow comics as an incorrigible cheapskate, Gottfried takes the bus to far-away gigs instead of flying and hoards every freebie he can get at hotels when he tours. In the storage bins crammed under every bed in their home, there’s nearly enough soap and shampoo emblazoned with Trump resort logos to wipe away the dirty feeling one gets upon seeing that name.

Berkeley does a bit of career recap here, collecting shock-laugh clips and letting others dissect how Gottfried sets audiences up with his squinting, nasal-voiced assault. But much of the career material here is about how Gottfried’s sense of humor gets him into trouble — as when he made “too early” jokes about the World Trade Center attack or the Japanese tsunami. Fellow comics like Bill Burr defend him, explaining how mocking a disaster isn’t the same as being unmoved. Regardless, Gottfried has lost plenty of work in the fallout of these incidents.

But Gilbert is less interested in the ups and downs of Gottfried’s public life than in showing what we’ve never seen. It listens to the performer talk about his rough relationship with his father and is especially attentive to the close friendship he has with his sister Arlene; in fact, the film veers off at one point, Crumb-like, to explore the sibling’s impressive body of work as a photographer. Less surprising is the pleasure Berkeley takes in seeing how this square peg fits into the easygoing family he has created with Kravitz. The sweetness he shows in this setting would likely be enough to convince many non-fans to give Gottfried the abrasive stand-up another chance. Those shocking, seemingly cruel one-liners sound different when you have a better idea where they’re coming from