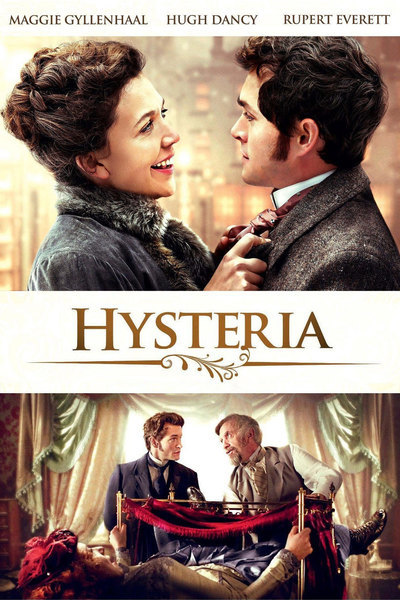

Hysteria

100 minutes | 35 mm

“First, do no harm,” the Hippocratic Oath admonishes doctors. By this standard, Dr. Robert Dalrymple must have been one of the few practitioners of the Victorian era with a sterling record. He knew no more than most other doctors of his time and was treating a condition that didn't exist, female hysteria. But give the doctor his due. His treatments consisted of inducing orgasms in his patients, and he didn't lose a one. In fact, his waiting room was usually jammed.

Tanya Wexler's quietly saucy “Hysteria” takes place in London at a time when medical authorities didn't know the word for or the concept of “orgasm,” and apparently many women never experienced them. His treatments consisted of modestly covering a patient's private regions with a little tent, reaching delicately beneath it and using digital stimulation to effect a cure. How he hit upon this method must be attributed to sheer genius.

We meet an ambitious young doctor named Mortimer Granville (Hugh Dancy), who has become nearly unemployable because of his habit of questioning the orthodoxy of the time. Desperate for work, he applies at the household of Dalrymple (Jonathan Pryce), who has more patients than he can handle. This also introduces him to the Dalrymple daughters, Charlotte (Maggie Gyllenhaal), a social activist, and the dutiful Emily (Felicity Jones), a student of phrenology who’s also searching for a husband. Charlotte flatly rejects her father’s theories as crackpot and his treatments as suspect, but uses family money to support her work among the London poor. Mortimer is intended to marry one daughter and falls in love with the other.

Curing hysteria is not a practice without its drawbacks, and Mortimer treats his patients with such dedication that he comes down with what was not then known as carpal tunnel syndrome. In despair, he consults his droll and dubious friend, Edmund St. John-Smythe (Rupert Everett), who happens to be toying with an electrically powered duster. They try it on Mortimer’s afflicted area, a light bulb illuminates over Mortimer’s head, and the vibrator is invented.

This milestone in human progress has never received the respect it deserves, and yet vibrators have been selling widely and well ever since, even in the early Sears catalogs. They were advertised with such euphemisms as “personal massagers” for aches and pains, although why most of them had phallic shapes was wisely left unexplained.

One of the pleasures of Wexler’s third feature is how elegantly it sets its story in the period. The costumes, the sets, the locations and the behavior are all flawless, and the British characters in the screenplay by Stephen Dyer and Jonah Lisa Dyer are all masters of never quite saying what they mean. Of course the Dalrymple practice is quite ethical, because there is no such thing as a female having pleasure from sex; the exact nature of the complaint being treated is sometimes described as “wandering uterus,” which for some reason makes me think of an albatross around its neck.

The film is based on fact. (“Really,” an opening title assures us.) The performances are spot on, and I especially like the spunky Gyllenhaal, who with this film and the underrated “Secretary” (2002), has built up a nice sideline in sexual exploration. The subject of vibrators has been under discussion after the publication of “The Technology of Orgasm” by Rachel Maines, and it was Wexler’s inspiration to see that the invention was all the more remarkable since it developed at a time when it treated a condition that officially didn’t exist. That was in contrast with many then-contemporary medical treatments, which didn’t treat conditions that officially did exist.