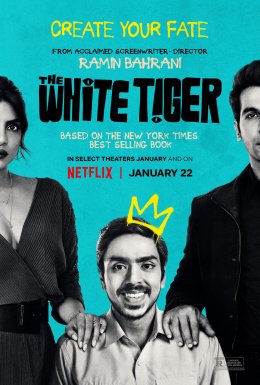

The White Tiger

Review by Roxana Hadadi

The films of Ramin Bahrani invite us to trespass into liminal space, and his sympathies are with the outsiders threatened to be left behind by those transitions. For the majority of his career, the first-generation Iranian American has extended unfussy empathy to people struggling to make sense of the ever-changing world and their place within it. In “Man Push Cart,” a Pakistani immigrant sells bagels and coffee out of a heavy cart he drags around Manhattan; in “Chop Shop,” a 12-year-old orphan tries to find enough work in Queens to support himself and his sister; in the bigger-budgeted “At Any Price” and “99 Homes,” Bahrani cast up-and-comers Zac Efron and Andrew Garfield, respectively, as young men whose hope in the American Dream is shattered by familial betrayal and economic devastation. Even in less-heralded work like his adaptation of the sci-fi classic “Fahrenheit 451,” Bahrani’s loyalty to the outcasts and underdogs—to those who can step back from the status quo and imagine how much effort it would take to destroy it—shines through.

In “The White Tiger,” Bahrani’s first cinematic excursion set outside of the capitalist voraciousness of the United States, the filmmaker—who both directed and wrote the screenplay for this adaptation of Indian author Aravind Adiga’s 2008 Booker Prize-winning novel—affixes his analytical eye upon the global underclass. Although less imaginative in his world-building style here than in his 24-hour-news-cycle approach to Ray Bradbury’s seminal text, Bahrani has maintained the darkly comedic, progressively resentful energy of Adiga’s debut. Like the work of Pakistani author Mohsin Hamid (in particular his 2008 novel The Reluctant Fundamentalist, which Mira Nair adapted into a 2012 film starring Riz Ahmed), Adiga’s “The White Tiger” is primarily concerned with the divide between the haves and have-nots, the injustice weathered by the latter from the former, and the inciting incident that could finally spark an uprising. Bahrani sticks close to the source material, trusting lead actor Adarsh Gourav to take us through the lifetime of poverty that could inspire a moment of radicalization, and that faith is warranted. Gourav hardens before our eyes in a performance that flits back and forth between immature recklessness, calcifying fury, and justified braggadocio, and that multifaceted quality is key to the intentionally uncomfortable rags-to-riches nature of “The White Tiger.”

Bouncing between the early 2000s, 2007, and 2010, “The White Tiger” follows protagonist Balram Halwai (Gourav, and played as a child by Harshit Mahawar), who narrates his life story as part of a letter written to the (now-former) Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao, who is visiting India. (A storytelling tactic lifted straight from the novel, that narration does get clunky here as an intrusion of international politics into an otherwise intimate story.) Balram is an entrepreneur, he boasts, but he came from nothing: He grew up in the rural town Laxmangarh, where his grandmother dictated every move. Although Balram was a strong student, his grandmother pulled him out of school to work at the family tea shop, hammering chunks of coal. His father died of tuberculosis. His brother was forced into an arranged marriage. The only way out of that lower-caste life was up, so when Balram overhears that the village’s Godfather-style landlord, nicknamed the Stork (Mahesh Manjrekar), is looking for a second driver for his returned-from-America son Ashok (Rajkummar Rao), Balram decides that person will be him.

The decision sets Balram on a path that he describes, in his narration, with a mangled combination of triumph and shame. He convinces his recalcitrant grandmother to give him the money for driving lessons in exchange for the majority of his future earnings. When he’s hired and moves into the Stork’s family compound in Delhi, he’s overly deferential and thoroughly obedient, taking on more tasks and continuously belittling himself to secure the family’s approval. Balram cleans rugs, sleeps on the floor, rubs oil into the Stork’s calves, and argues that he deserves a fraction of the already-small salary they offer. Much of this inferiority is inbred, Balram says, the result of thousands of years of a rigid caste system (“men with big bellies and men with small bellies”), magnified by hundreds of millions of people fighting for the same low-paying jobs, amplified even further by the gap between India’s poor, both rural and urban, and the increasingly out-of-reach wealth horded by a few. Balram has been angry for a long time, and the charged attitude of his present narration bleeds into the past, coloring his interactions with the Stork and his family as we sense that something awful, some violence that no amount of money can fix, is coming.

What “The White Tiger” wonders—as do Bong Joon-ho’s “Parasite” and Ken Loach’s “Sorry We Missed You,” films that would pair nicely thematically with this one—is whether wealth can ever be divorced from the inherent privilege it provides. Ashok and his wife Pinky (Priyanka Chopra Jonas) seem different from the rest of the family (Ashok broke caste custom to marry Pinky; Pinky asks Balram what he wants to do with his life), but how much of that compassion is meant to make themselves feel better? When they treat Balram like he’s from a different world, when they praise him for knowing the “real India,” when they take at face value his farcical stories about rural religious customs, aren’t they just as condescending as the rest of Ashok’s family? When they ask Balram to dress up like the stereotypical image of a British maharaja for Pinky’s birthday, aren’t they essentially mocking him for being willing to take their mockery?

Rao and Chopra Jonas work well together as individuals who occupy two spaces at once: As much as they try to distance themselves from the familial wealth that protects them from the surrounding world, as much as they argue with the Stork for the insults that he hurls toward Balram, as much as they ask Balram about himself and encourage him to set higher standards of behavior, they still consider themselves better. They are, like the Park family in “Parasite,” unable to understand how offensive their very existence is to someone like Balram, and how much worse their moments of kindness make that disparity. When Balram sees Ashok for the first time, Bahrani gives the moment a sort of romantic veneer: Ashok in slow motion, an upswell of music, Balram saying dreamily, “This was the master for me.” But scene by scene, “The White Tiger” punctures the fantasy that a rich man could also be a nice man, and although the comedy here is pitch-black, it strums with a particularly focused anger.

Some of the text from Adiga’s novel doesn’t have the same lyricism said out loud as it did on the written page, most noticeably the book’s central theme of poor Indians being stuck in a “rooster coop.” Toward the end of the film, there are a few endings too many, and that extra time dampens the impact of a certain shocking act. Elsewhere, however, Bahrani’s script emphasizes certain dialogue that captures Balram’s sense of unity with who Noam Chomsky would call the world’s “unpeople” (“I think we can agree that America is so yesterday … The future of the world lies with the yellow man and the brown man,” Balram writes in his letter), and as he did with Michael B. Jordan’s Guy Montag in “Fahrenheit 451,” Bahrani uses mirror images and duplicates to communicate Balram’s fractured sense of self. He finds contrast between the Balram who retreats into the gilded elevator in Ashok’s apartment building to pinch his hand to keep from crying, and the Balram who loses his mind at a beggar woman on the streets far below the apartment—but which reaction is genuine? What kind of person is Balram becoming?

“Straight and crooked, mocking and believing, sly and sincere, all at the same time,” Balram says of the formula for success at the beginning of “The White Tiger,” Bahrani’s fish-eye lens giving us a warped sense of perspective. When Bahrani visually breaks the fourth wall again in the film’s final moments, evoking the grander themes of disruption he’s mined during the preceding two hours, the deliberate provocation he offers is as successfully acidic as the rest of “The White Tiger.”