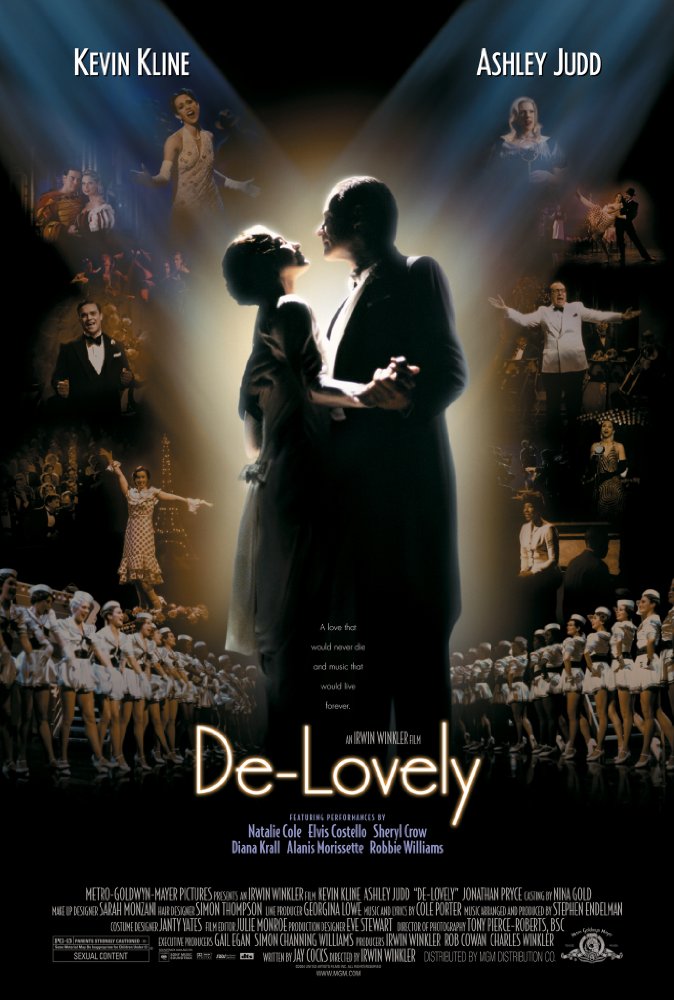

De-Lovely

125 Minutes | Blu-Ray

Roger Ebert, RogerEbert.com

“I wanted every kind of love that was available, but I could never find them in the same person, or the same sex.” — Cole Porter

Porter floated effortlessly for a time between worlds: Gay and straight, Europe and America, Broadway and Hollywood, show biz and high society. He had a lifelong love affair with his wife, and lifelong love affairs without his wife. He thrived, it seemed, on a lifestyle that would have destroyed other men (and was, in fact, illegal in most of the places that he lived), and all the time he wrote those magical songs. Then a horse fell down and crushed his legs, and he spent 27 years in pain. And still he wrote those magical songs.

“De-Lovely” is a musical and a biography, and brings to both of those genres a worldly sophistication that is rare in the movies. (If you seek to find how rare, compare this film with “Night and Day,” the 1946 biopic which stars Cary Grant as a resolutely straight Porter, even sending him off to World War I). “De-Lovely” not only accepts Porter's complications, but bases the movie on them; his lyrics take on a tantalizing ambiguity once you understand that they are not necessarily written about love with a woman:

It’s the wrong game, with the wrong chips

Though your lips are tempting, they’re the wrong lips

They’re not her lips, but they’re such tempting lips

That, if some night, you’re free

Then it’s all right, yes, it’s all right with me.

It would appear from “De-Lovely” that on many nights Porter was free, and yet Linda Lee Porter was the love and solace of his life, and she accepted him as he was. One night in Paris, they put their cards on the table.

“You know then, that I have other interests,” he says.

“Like men.”

“Yes, men.”

“You like them more than I do. Nothing is cruel if it fulfills your promise.”

Dialogue like this requires a certain wistful detachment, and Kevin Kline is ideally cast as Cole Porter: elegant, witty, always onstage, brave in the face of society and his own pain. Kline plays the piano, too, which allows the character to spend a lot of convincing time at the keyboard, writing the soundtrack of his life. But who might have known Ashley Judd would be so nuanced as Linda Lee? In those early scenes, she lets Porter know she wants him and yet allows him his freedom, and she speaks with such tact that she is perfectly understood without really having said anything at all. Yet their relationship was by definition painful for her, because it was really all on his terms. Many of his lyrics are fair enough to reflect that from her point of view:

Every time we say goodbye, I die a little, Every time we say goodbye, I wonder why a little, Why the Gods above me, who must be in the know. Think so little of me, they allow you to go.

Cole and Linda met in Paris at that time in the ’20s when expatriate Americans were creating a new kind of lifestyle. Scott and Zelda were there, too, and Hemingway, and the movie supplies as the Porters’ best friends the famous American exile couple Sara and Gerald Murphy (the originals for Fitzgerald’s “Tender is the Night”). Porter was born with money, made piles more and spent it fabulously, on parties in Venice and traveling in high style. Linda’s sense of style suited his own: They always looked freshly pressed, always seemed at home, always had the last word, even if beneath the surface there was too much drinking and too many compromises. The chain smoking which eventually killed Linda was at first an expression of freedom, at the end perhaps a kind of defense.

The movie, directed by Irwin Winkler (“Life as a House”) and written by Jay Cocks (“The Age of Innocence”), is told as a series of flashbacks from a ghostly rehearsal for a stage musical based on Porter's life. Porter and a producer (Jonathan Pryce) sit in the theater, watching scenes run past, but the actors cannot see or hear Porter, and the producer may in a sense be a recording angel.

This structure allows the old, tired, widowed, wounded Porter to revisit the days of his joy, and at the same time explains the presence of many musical stars who appear, both on stage and in dramatic flashbacks, to perform Porter’s songs. Porter has famously been interpreted by every modern pop singer of significance, most memorably by Ella Fitzgerald in “The Cole Porter Songbook,” but here we get a new generation trying on his lyrics: Elvis Costello, Alanis Morissette, Sheryl Crow, Natalie Cole, Robbie Williams, Diana Krall.

The movie contains more music than most musicals, yet is not a concert film because the songs seem to rise so naturally out of the material and illuminate it. We’re reminded how exhilarating the classic American songbook is, and how inarticulate so much modern music sounds by contrast. Kline plays Porter as a man apparently able to write a perfect song more or less on demand, which would be preposterous if it were not more or less true. One of Porter’s friends was Irving Berlin, who labored to bring forth his songs and must have given long thought to how easy it seemed for Porter.

If the film has a weakness, it is that neither Cole nor Linda ever found full, complete, passionate, satisfying romance. They couldn’t find it with each other, almost by their terms of their arrangement, but there is no evidence that Porter found it in serial promiscuity, and although Linda Lee did have affairs, they are not made a significant part of this story. They were a good fit not because they were a great love story, but because they were able to provide each other consolation in its absence.

“Strange, dear, but true, dear,” he began a song which confessed:

Even without you, My arms fold about you, You know, darling, why, So in love with you am I.