Cold War

Tomris Laffly

December 17th, 2018

Unattainable desire hurts deeply, scars permanently and like in “Casablanca,” “Passionate Friends” and countless others, makes for some of film history’s most swoon-worthy stories of passion. An aching film on such exquisite pains of impossible love, Paweł Pawlikowski’s “Cold War” concurrently swells your heart and breaks it, just like the sore memory of a lover that drifted away from your life, or an intensely craved kiss that never was. It’s a tale with the makings of legendary sagas, following the union and break-up (and union and break-up again and again) of Wiktor and Zula, a classically gorgeous couple from the opposite sides of the tracks. They first meet deep in the dilapidated countryside of the post-World War II Poland. They exchange suggestive glances and embark on a stormy affair that disastrously evolves over two isolating decades and numerous unsympathetic locales across Europe.

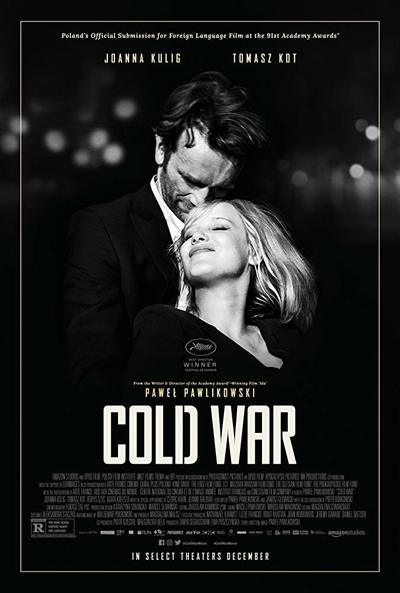

While ageless and universal, “Cold War” comes from a deeply personal place for Pawlikowski—Wiktor and Zula are based on and named after Pawlikowski’s own parents, who (as the filmmaker openly voices in every interview) had their own thundery relationship battle that stretched over four decades. In this cinematically condensed, informally episodic version (jazzy and unruly like some of the film’s music), the attractive duo is played by the striking Tomasz Kot and the immensely talented actor/singer Joanna Kulig; an instant, Marilyn-Monroe-meets-Liv Ullmann-esque vision.

A sophisticated conductor and musicologist traveling through Poland with his producer Irena (Agata Kulesza) and recording folk tunes with the hopes of reintroducing their glorious melodies, Wiktor auditions talent after talent for the choral ensemble he is tasked to create. It’s during one of those tiring sessions that the fiery Zula enters the picture. She sings well; she says she can easily learn to dance and in what might be a con to leave a lasting impression, claims she once stabbed her abusive father fatally. Falling for her directness and turbulent spirit immediately, Wiktor recruits her. And the impossible obstacles introduce themselves in no time once their affair takes off in earnest.

Nostalgically shot in sterling black and white and the boxy Academy aspect ratio by cinematographer Lukasz Zal (like Pawlikowski’s “Ida,’ a heartbreaking study of the pull of identity), “Cold War” is really a film about the hardships of living in exile. In that, the starry-eyed Wiktor and the hardened Zula make and break promises, support and betray each other, and both abandon and reassume identities to survive wherever life takes them within or on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Their brief bliss while traveling and making music together gets cut short when Zula doesn’t turn up for their haphazardly planned escape from Poland. When they meet years later in the cobblestone streets of Paris and reinstate their impossible romance in the smoky corners of jazz clubs filled with snobby intellectuals who look down on Zula, their odyssey takes an even more impossible turn: Zula plays up her national pride—a form of self-defense any immigrant will relate to. She can no longer stand the submissive, alienating man Wiktor has become.

And yet, their love for each other never dies; it instead takes on renewed shapes and forms. Expertly braiding the historical canvas of the '50s and '60s and the era’s music into the lovers’ affair (this is one soundtrack you will quickly want to get your hands on), Pawlikowski (along with his co-writers Janusz Głowacki and Piotr Borkowski) both honors and attempts to make sense of his parents’ chaotic togetherness. But most of all, he hits a timeless cinematic nerve that pulsates with euphoric verve. The tragic yearning in the impossibly sexy “Cold War” is so palpable that it makes you feel thankful to be alive with human feelings, heartbreaks of the past be damned.