In & Of Itself

Review by Matt Fagerholm

THE WIZARDRY OF FRANK OZ: WHY YOU MUST SEE “IN & OF ITSELF”

It has been exactly one month since I saw Frank Oz’s “In & Of Itself” at the Daryl Roth Theatre in New York City. Ever since that unforgettable evening, not a day has gone by that I haven’t thought about it. I’ve debated whether to write anything about it, apart from a rave I posted on social media, since I wouldn’t dream of revealing any of the mind-boggling surprises that occur during the 75-minute running time of this one-man show, written and performed by award-winning magician Derek DelGaudio. However, since the play is scheduled to end its tremendously successful extended run in only two months, I couldn’t resist penning the following article, if only to encourage you not to miss it. “In & Of Itself” is not only the most astonishing live show I’ve ever seen, it may very well be the crowning achievement of Mr. Oz’s career, which is saying something, considering the career he’s had.

No living artist or entertainer has impacted my life more profoundly than Oz has, beginning with his timeless portrayals of such beloved characters as Miss Piggy, Fozzie Bear, Bert, Animal, Sam the Eagle, Grover, Cookie Monster and Marvin Suggs, to name a few. Together with Muppet creator Jim Henson, Oz formed one of the great duos in screen history. The meticulous nuance and depth of emotion that they brought to their characters, whether as Ernie and Bert or Kermit and Piggy, caused us to lose ourselves entirely within the illusion. We regarded them not as puppets but as fully dimensional beings whose every movement, or lack thereof, spoke volumes about their inner lives. What matters most of all to Oz, in any artistic endeavor, is maintaining honesty in the world that one is creating. The best kind of acting shouldn’t draw attention to itself. We quickly forget about the puppeteer while watching Piggy in “The Muppet Movie” or Yoda in “The Empire Strikes Back” because every gesture they make and flicker of emotion on their faces feels utterly organic. They are alive.

As soon as I heard that Oz and his wife, Victoria Labalme, had made a documentary, “Muppet Guys Talking,” that would be released exclusively online this past March, I knew that I had to write about it for RogerEbert.com. Getting the chance to chat with them about their marvelous film—one of the year’s best—was an honor beyond compare. In many ways, it’s the picture Muppet fans have been hoping for ever since Henson’s untimely passing in 1990. With refreshingly informal candor, veteran Muppeteers Dave Goelz (Gonzo), Fran Brill (Prairie Dawn), Bill Barretta (Pepé the Prawn) and the late Jerry Nelson (Count von Count) join Oz in reminiscing about the nurturing and adventurous working environment established by Henson, who is dubbed “a harvester of people.” Though he’s renowned for his collaborations with Henson, Oz told me that he doesn’t consider himself a puppeteer. “Puppets don’t mean much to me,” he said. “I’m interested in characters, which is why the Muppets are so singular. There are no real characters in the world of puppets like the Muppets.”

Henson aimed to achieve the impossible, as evidenced by the jaw-dropping feats in his 1981 feature directorial debut, “The Great Muppet Caper,” a few of which are discussed in “Muppet Guys Talking” as well as the invaluable supplemental footage (available on the documentary’s official site to Below Stage Pass members). Consider the opening sequence of “Caper” where Fozzie, Kermit and Gonzo are riding in a hot air balloon. A less imaginative filmmaker would’ve opted for back projection, but Jim decided to utilize an actual airborne balloon flying a thousand feet off the ground, inhabited by three remote controlled puppets performed by Oz, Henson and Goelz from a nearby helicopter. Suspended from a second helicopter was a cameraman capturing the footage while situated on a sling. Oz’s interest in character over spectacle shone through in his equally impressive 1984 solo directorial debut, “The Muppets Take Manhattan,” which brought newfound complexity to the relationships between Kermit and the gang. There’s a wonderful scene featuring Kermit, Piggy and Gregory Hines in Central Park, where the camera created shots of various scales—tight, medium, and wide—without ever cutting away (a technique Oz admired in Orson Welles’s work), allowing the audience to savor the trio’s interaction for over two minutes of unbroken screen time.

When I mentioned this technique to Oz, he said that it reflected his belief in the importance of contrasts, not just in terms of lighting or cinematography but in life. “If you love somebody, contrast is important because if they’re exactly like you, then you might as well start loving yourself,” Oz noted. Ernie’s extroverted nature and Bert’s deep-seated insecurity would never have rung true if it hadn’t spawned naturally from the men who played them. In Derek DelGaudio, Oz has found perhaps his most meaningful collaborator since Henson, and contrast is every bit as essential in their work together. During an interview last year with Lawrence O’Donnell (embedded above), Oz confessed that he isn’t a “magic geek,” and prefers not to know how a magician’s tricks are done. He connected with DelGaudio through their shared love of pushing the form through experimentation. In the extras for “Muppet Guys Talking,” Oz recalls the monthly trips he and Jim took in the 1960s to the Filmmakers’ Cinemathèque, which screened the work of visionaries like Warhol and Brakhage. Though some of the programming left Oz underwhelmed, Henson said “there might be one thing that’s great” in each picture that they could learn from.

Henson’s Oscar-nominated 1965 short film, “Time Piece,” is a masterpiece of existential artistry, charting a man’s frenzied efforts to outwit the relentless passing of time. Oz made two cameos as an office messenger boy and a man in a gorilla suit. “Jim Henson began as an experimental filmmaker (actually an experimental everything-maker),” Oz wrote via Twitter on April 8th. “He took many detours in his life, finally coming back years later to projects he would not have been able to do had he not taken those detours.” In a separate post, he wrote, “I was speaking with my wife about detours. I’ve done so much. I feel privileged. But still, it all feels like a detour. Only now, working with Derek to create ‘In & Of Itself’ do I feel I’ve really come home to my real self; my fearless and rebellious self.” That concept of the real self versus the identities imposed on us by others is, of course, the central theme of the show. DelGaudio told O’Donnell that the luxury of this theme, which spawned from his own life, is that it never ends. We are always “being someone” and always “being seen” by other people, resulting in the existential crises that permeate our everyday encounters. After finding acceptance and friendship in my high school theatre community, I found it difficult to shed the heightened neurotic persona I cultivated in various shows when I was offstage. This resulted in me being branded a “comic relief” among my peers, an identity that gave me comfort, though it limited my growth in other areas.

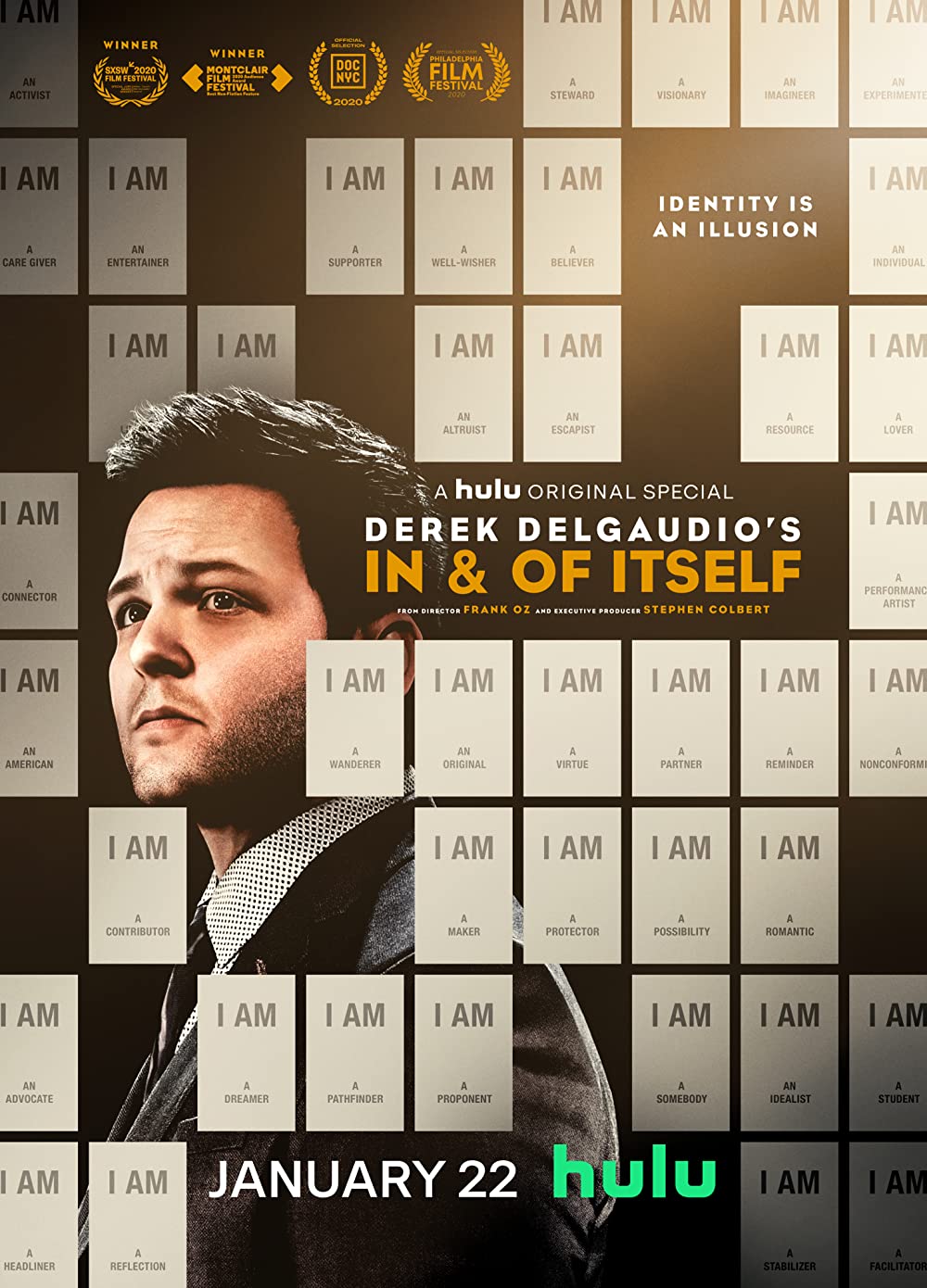

I won’t go into detail about what happens during DelGaudio and Oz’s show, but I will explain what occurs just beforehand. As you are ushered into the theater, you find yourself faced with a wall of alphabetized cards, each displaying a particular identity. A woman standing nearby instructed me to choose a card that personally spoke to me, and I ended up taking the one that Oz would’ve likely avoided: “I Am a Puppeteer.” After all, it was the first profession I ever dreamed of having as a child whose favorite show was “Sesame Street” and whose first crush was Miss Piggy. Yet it was the humanism in Henson’s philosophy that left the most indelible mark on my soul. If he could get us to empathize with creatures crafted from foam and felt, then perhaps we could feel empathy for our fellow living beings on this earth as well. “How we perceive each other is very limiting,” Oz told O’Donnell, while stressing that the show demonstrates how each person is much more than just one thing. By transcending our preconceived notions of ourselves and those seated around us, the audience that sees “In & Of Itself” gradually transforms from a roomful of strangers into a surrogate family united in awe and euphoria. I have no doubt Henson would’ve loved it.

It was Mr. Oz himself who invited me to see his show, and it was an invitation my sister and I couldn’t refuse. I knew nothing about DelGaudio prior to seeing “In & Of Itself,” and when he first stepped onto the stage, I initially thought he was an audience member who hadn’t yet found his seat. So unassuming was his behavior and so measured was his voice that he caused the 150 people in attendance to lean forward, listening carefully to his hypnotic, often heartrending stories. Only afterward did I realize that the woman sitting next to me was the magician’s cousin, who informed me that each memory from DelGaudio’s past that he shared with the crowd was entirely true. During one particularly dramatic moment, DelGaudio stood mere feet away from me as he delivered a powerful monologue while crying real tears. Never for a moment did it appear as if he were “acting”—he was simply being—all the while guiding our attention without us realizing it (like the skilled camerawork in a Welles film). When Oz came aboard the project, he took the fragments of DelGaudio’s blueprint and helped connect them in a way that made the entirety of the show—like the entirety of a Muppet—feel alive. As much as he speaks during the show, DelGaudio conveys a great deal of his internal struggle nonverbally, as Mark Mothersbaugh’s score (which has haunted my dreams ever since) accentuates the unfolding mystery.

The rigorous specificity of DelGaudio’s illusions are not unlike the painstaking detail of Oz’s puppeteering, both of which are brought to life by the performer’s uncompromising honesty. It’s impossible to leave “In & Of Itself” without forming your own thoughts about the illusory essence of identity. To me, Kermit’s “real self” has no relation to the sanitized mascot favored by Disney and is more akin to George Bailey from “It’s a Wonderful Life”—a good soul prone to frustration who is ultimately saved by the community he built. Bailey is a lot like my father, a man who had plans for his future that were disrupted by the cruel turns of life. He has spent the years following his retirement as a full-time caregiver for my mother stricken with Multiple Sclerosis, and this identity has begun to engulf the others that have defined his life: social worker, friend, brother, frustrated actor, part-time rapper, Abe Lincoln enthusiast, even husband. Illness can also overtake one’s identity, though my mother has never allowed herself to be defined by her disease. Apart from reawakening our childlike sense of wonder, the great gift of “In & Of Itself” is in how it affirms that each of us is—and deserves to be seen as—more than just one thing. Frank Oz is not just a Muppeteer. He is an actor, a director, a humanist, a father, a husband, a rebel, one of our finest entertainers and, in my opinion, an artist of the highest order. “In & Of Itself” may close in two months, but it will forever remain in my heart.