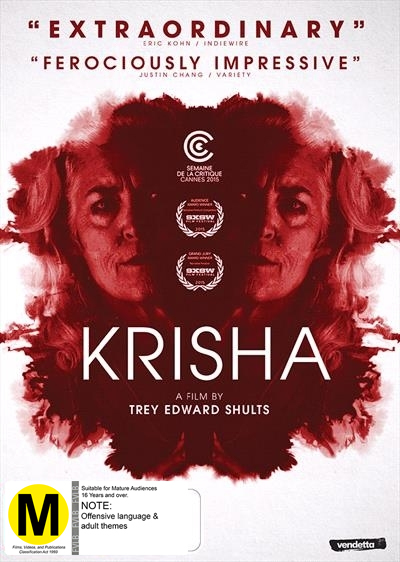

Krisha

Watching "Krisha" is a revelation: there are expected "rules" for such material (a former addict returns home for a holiday), but then director/writer Trey Edward Shults breaks every rule, making those rules seem tired and arbitrary in the process, and he does so with bravura, confidence, flash. While the style is in-your-face, every element of it (a show-stopping score by Brian McOmber, Drew Daniels' camera-work, Shults' editing) is in service to the story, and to the story beneath the story, how destroyed this family has been by Krisha's addiction. "Krisha" (which won the Grand Jury prize at the 2015 SXSW Film Festival) is an assault, from the first unforgettable moment on, and Shults' style clues you in from the get-go that this won't be your familiar "addiction/redemption tale." This is going to be something very, very different. This tour de force is even more astonishing when you learn that it is Shults' first feature.

Krisha (Krisha Fairchild), an older woman with flowing grey hair and a body rolling with curves, returns to the family home for Thanksgiving, after presumably decades lost to addiction. (As she pulls up to the curb outside the house, the hem of her dress sticks out from the bottom of the car door. That detail says it all.) She's sober now and desperate to re-enter the family circle. Her presence at Thanksgiving is a test after years of letting everyone down and ruining family gatherings. She has promised to cook the Thanksgiving turkey, a big job (considering the number of people present), but she's happy to take on the responsibility because it will prove she's got her act together, she's a good girl now, they can trust her.

The family gathered is multi-generational. There is Krisha's sister Robyn (Robyn Fairchild) and Robyn's technologically-challenged husband (who can't figure out his phone, his computer, or the remotes), their kids, the kids' spouses, cousins, plus a newborn, plus Krisha's ancient mother. The house is open on the first floor, rooms pouring into other rooms, a tiled floor with no rugs to absorb the noise. The voices bounce off the walls, total cacophony, creating a believable atmosphere of a rambunctious, close family. Krisha enters, and people line up to hug her, happy that this lost lamb might be on the right track finally. But there's a formal quality to the reunion. The family has been hurt deeply by Krisha. She has missed decades in their lives. One of the kids (Shults himself) keeps his distance, even when she clutches him to her. He pats her back stiffly, retreats.

Over the course of the next couple of hours, Krisha prepares the turkey, (at one point the bandage on her finger—a finger missing its tip from some unexplained catastrophe—disappears inside the bird), sneaking out to smoke butts on the patio, or retreating to the bathroom upstairs to stare at herself in the mirror, trying to calm down. The cousins, all boys around the same age (high school and college), have arm-wrestling contests, watch football, sneak off to watch porn upstairs, play boardgames. The family has moved on without Krisha, the space she used to take up is no longer there.

"Krisha" is both realistic and deeply surreal. Shults leaps around visually, from the nephews wrestling in the yard, to Krisha tearing the kitchen apart looking for the oven-timer, the camera whirling around her in dizzying 360-degree turns, to Robyn and her husband having whispered worried pow-wows in the corner, as Krisha peeks at them anxiously. The noise is deafening inside the house, but the sound drops out when Krisha is alone. The frantic score would be appropriate for a horror film, and in a lot of ways "Krisha" is a horror film (the first moment evokes pure psychological terror).

Cooking that turkey is a cliffhanger in and of itself. As the film hurtled on its rickety precarious rails, I kept thinking about the turkey in the oven. I wanted her to go check on it. It seemed so important that the turkey come out well. It wasn't just a turkey. It was life-or-death. Shults' immersive style drove that home in ways both funny and terrifying. The tension, at times, was unbearable.

Krisha stands at the center, staring around her with wild eyes, desperate for a drink, for belonging and forgiveness. She's a tough-looking broad with a big belly laugh, but her hopes are hanging by a thread. "You are heartbreak incarnate," declares her caustic brother-in-law. "You are a leaver." Not only does he have a point, he is right. Krisha talks about learning to "be a better person" and how she has been trying to get in touch with her "spirituality," but there's something "off" in her attitude, considering the damage she's done.

Krisha Fairchild is Shults' aunt, who has done mostly voiceover work. To say her performance is "good" doesn't even cut it. It helps that she is an unknown face. She doesn't look like a Hollywood actress playing at being an addict. She looks like the real thing. Her mere presence calls into question the industry's casting choices: who else might be out there not getting work because of their body or their age? Krisha is a mess. She tries hard. She struggles into her way-too-fancy red dress for the upcoming dinner. She's buoyant and fragile, self-pitying, clueless. It's amazing just watching her, and Shults gives us multiple still moments where the camera stares at her profile, her reflection in the mirror, her face gazing out a window. The movie is all about her face. There are moments when she goes totally blank, a void in her eyes. It's deeply unnerving.

The story behind shooting "Krisha" is almost as extraordinary as the film itself. Shot over nine days in the Texas home of Shults' parents, the cast is made up of members of Shults' family (most of them are not actors). In interviews, Shults and his family are quite open about the fact that the film is based on their shared experience with an addict relative. The film feels like a blazing catharsis for all involved. Shults' mother (a therapist in real life) has a scene with Krisha in an upstairs bathroom that is so pained, so raw, that it puts other confrontation scenes in other films to shame.

We all know how addiction narratives usually play out (at least in the movies). The addict shows up, there are tense scenes, shouting matches, maybe a relapse, but in the end, there is hope after all. People in the real world know that not every "addiction tale" has "redemption" at the end of it. How many chances are you supposed to give someone before you back off in self-protection? "Krisha" is not just about its main character but about the effect her alcoholism has had on the family. They are right to be wary of her. They are right to keep their distance. She really is "heartbreak incarnate."