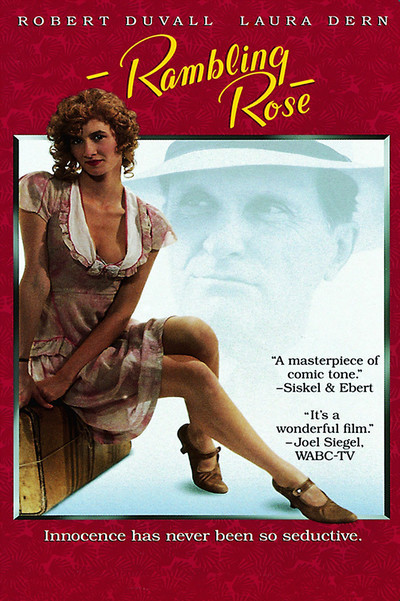

Rambling Rose

112 min | 35mm

Here is a movie as light as air, as delicate as a flower.

Breathe on it and it will wither. It tells the story of an impossibly sweet and strange Southern family, and the troubled teenage girl who comes to live with them, and brings a sharp awareness of carnality under their roof, with only the most cheerful of results. The screenplay by Calder Willingham is based, I have heard, on autobiographical reminiscence, but nostalgia in this case has bestowed a lot of benevolence onto the past.

The year is 1935. The Hillyer family lives in a spacious old Southern manse with a big lawn and lots of trees and porches, overlooking the road that crosses the creek. There’s Daddy (Robert Duvall) and Mother (Diane Ladd) and Buddy (Lukas Haas) and a couple of other kids. One day Rose (Laura Dern) comes to stay with them, walking up the path, swinging her cardboard valise like a calling card. She is 19 years old, and has gotten into unspecified troubles with unspecified men, and to Buddy, who is 13, this is a high recommendation.

Daddy is a lawyer who has invited Rose to come and stay with the family, not as a maid but as a guest. “Rosebud,” he tells her, “I swear to God you are as graceful as a capital letter ‘S.’ You’ll give a glow and a shine to these old walls.” And so she does, bringing as well a glow and shine to Buddy’s nocturnal imaginings and adolescent fantasies.

What is special about “Rambling Rose,” however, is the way love takes first place ahead of sex. Although the materials of the story are lurid—Rose is a “borderline nymphomaniac,” the local doctor concludes—neither Daddy nor Mother seems shocked by her behavior or flamboyant style of dress. They understand that she has been through some hard times, they accept her as she is, they hope to give her some help in life.

For Buddy, who is at that age when a whisper of decolletage is worth a roomful of schoolbooks, Rose is a godsend. He is fascinated by her guileless sexuality, and there is a breathless scene where he essentially conducts a natural history field trip across her upper body. But Rose is not really interested in Buddy.

She loves Daddy with a fierce burning passion, because she admires him so much—worships him, and is eternally grateful that he rescued her from those unspecified men. The way that Duvall handles her passionate advance is one of the treasures of this film.

“Rambling Rose” was directed by Martha Coolidge, and probably benefitted from being made by a woman. Men, I think, are sometimes too single-minded about sex. Bring up the subject, and it’s all they can think about. Coolidge takes this essentially lurid story and frames it with humor and compassion, putting sexuality in context, understanding who Rose really is, and what stuff the family is really made of.

The plot in “Rambling Rose” is slight and elusive; if it were not for a framing device, it might almost have none. The movie is all character and situation, and contains some of the best performances of the year, especially in the ensemble acting of the four main characters. Laura Dern finds all of the right notes in a performance that could have been filled with wrong ones; Diane Ladd (her real-life mother) is able to suggest an eccentric yet reasonable Southern belle who knows what is really important; Robert Duvall exudes that most difficult of screen qualities, goodness, and Lukas Haas (the boy in “Witness”) brings to his study of Rose such single-minded passion you would think she was a model airplane.