Won't You Be My Neighbor?

Odie Henderson

June 8th, 2018

“Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” presents the history of Fred McFeely Rogers, Presbyterian minister, children’s advocate and the most beloved Republican since Abe Lincoln. Like Honest Abe, Mr. Rogers was known for wearing a specific article of clothing and his ability to sweet talk a Congressman or two. From 1968 to 2001, Mr. Rogers kept millions of little ones out of their parents’ hair by offering a half hour program designed to counter the cartoon violence and frenetic pacing of practically every other kids’ show on the air. On PBS, he sang, offered advice and worked a cat puppet whose feline vocal tic drove my mother absolutely insane. 15 years after his death, the heroic endeavors of Fred Rogers are finally being celebrated on the big screen.

One of the many “stand up and cheer” moments in Morgan Neville’s enchanting documentary, at least for me, is when cellist Yo-Yo Ma describes his first meeting with the man who will forever be known as the proprietor of “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.” “He scared the hell out of me,” says Ma. I felt vindicated, because when I was a kid, Mr. Rogers terrified me too. He made me nervous, a condition exacerbated by my cousin telling me that he was actually a serial killer. According to her, Mr. Rogers lured people on his show and then decapitated them with the Museum-Go-Round.

Whatever Mr. Rogers was up to, watching his show made me uneasy; he was just too mild-mannered, too quiet and too calm. That felt odd, because the environment of my upbringing was anything but calm and quiet. My sister thought he was magical, though, proving that old adage about girls figuring out things long before boys do. Eventually, I came around to her way of thinking, and it only took 24 years before I realized just what it was that made Mr. Rogers so beloved and so effective.

More on that later. “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” puts to rest many of the most common rumors about Mr. Rogers. It does so in the same blunt yet understated way that its subject dealt out information to kids. The “torso full of tattoos” rumor is addressed by showing Mr. Rogers swimming his daily mile in the local pool. To my chagrin, there’s no mention of on-set violence featuring buildings from the Land of Make Believe, but the film makes up for that by revealing the inspiration for the puppet who lived inside the Museum-Go-Round. It’s a hilarious moment that shows that respectable Mr. Rogers could also be mischievous—and petty!

Rather than rely on celebrities or viewers espousing what Mr. Rogers meant to them, “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” makes judicious use of a few people closest to the man or his neighborhood. These include his wife, Joanne and their children plus castmembers David “Mr. McFeely” Newell, François “Officer Clemmons” Clemmons and Joe “Handyman” Negri. Negri in particular makes the neighborhood set sound like a riotous party, but everyone leans into the idea that, under Mr. Rogers' sweet exterior was a true radical. And maybe even a clairvoyant: In a clip from the Neighborhood’s first week on the air, the Land of Make Believe’s “benevolent monarch” puppet King Friday XIII issues a proclamation to build a wall to keep “undesirables” out!

“Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” makes this “he’s a radical” idea credible. After all, a troublemaking idea existed in the titular song that Mr. Rogers sang to the kiddies at the beginning of each show. Here was a White man inviting everyone to live in his ‘hood, regardless of color. “I have always wanted to have a neighbor just like you,” he sings, a sentiment that wasn’t shared by most Americans in the still-segregated era when "Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood" premiered. (Eddie Murphy’s brilliant parody, “Mister Robinson’s Neighborhood,” excerpted here in a brief clip, seizes upon this “Fear of a Black Neighbor” notion and runs with it.) But Mr. Rogers’ true genius was showing by example, and Neville highlights two memorable instances of this.

The first is Mr. Rogers’ early appearance before Congress on behalf of funding for LBJ’s newest creation, the Public Broadcasting System. Facing an adversarial Senator Pastore, who had already made up his mind to pan PBS, Mr. Rogers makes his argument by simply reciting the words to a song he had written for his show. Pastore folds immediately. “You’ve just earned your $20 million,” he says. You wouldn’t buy this in a Jimmy Stewart movie—and God help us if this had to play out in today’s Washington D.C.—yet you can find this fascinating footage on YouTube.

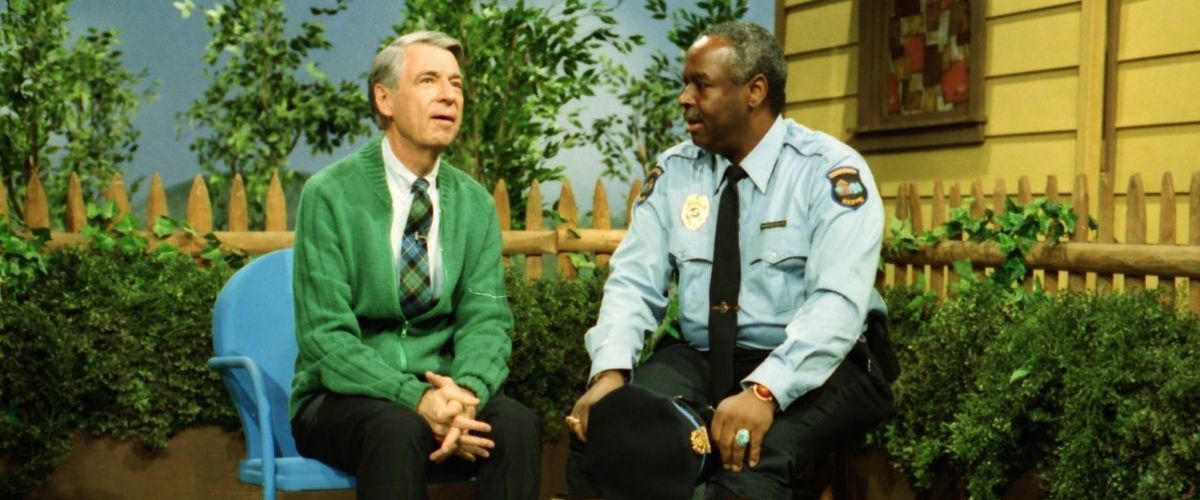

The second instance of Mr. Rogers leading by example occurs with the character of Officer Clemmons. As an African-American, Clemmons was at first hesitant to play a cop on the show, but he realizes the importance of kids of color seeing a friendly, familiar-looking face as law enforcement. Even more importantly, he participates in a bit where Mr. Rogers basically gives the finger to the notion of segregated swimming pools by inviting Clemmons to join him in a very small wading pool. Neville intercuts this scene from the show with footage of White lifeguards pouring bleach into a pool where Black kids were swimming.

Clemmons also figures in an incident where Mr. Rogers wasn’t so enlightened. Someone from the show discovered that the then-closeted at work Clemmons had been to a gay bar. “I had a good time!” says Clemmons, who was then told that any future bar visits would result in his termination from the show. I can only imagine which Land of Make Believe puppet got tasked with informing Clemmons that Mister Roger’s Neighborhood did not have a Castro District. (I hope it was Henrietta Pussycat saying “meow meow gay bar meow meow nuh-uh meow meow fired!”) But at least Clemmons informs us that Mr. Rogers “eventually came around” to acceptance.

“Love is at the root of everything,” Mr. Rogers tells us in an early clip, “or lack of it.” Like his fellow puppeteer and PBS colleague Jim Henson, Fred Rogers used puppets to deliver much of his message. His first puppet, Daniel Striped Tiger, serves as an animated avatar between segments because, as Mrs. Rogers points out, Daniel was an evocation of her husband’s childhood feelings of insecurity and his need to be loved. It’s hinted that Mr. Rogers was bullied as a heavyset kid—he was called “fat Freddie” and picked on, which may have led to his insistence in adulthood that a child’s feelings were as important as any adult’s. Folks are quick to point out, however, that while Daniel represents innocence, Mr. Rogers also does the voice of King Friday XIII, who clearly represents that adult need to always get one’s way.

Looking at “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” with adult eyes is rather fascinating. You notice that there’s a clear distinction between imagination and reality—we’re never lead to believe that the puppet segments are anything but pretend, for example. Mr. Rogers never talks down to his viewers, nor does he really sugarcoat uncomfortable things like anger or death. He’s very matter of fact, and his manner was deliberate, constant and repetitive. Which leads me to my moment of Mr. Rogers clarity.

Many years ago, I’d come home from my Wall Street job in a state of great agitation and upset. I was stressed out, worn out and miserable beyond measure. I absent-mindedly turned on the television and went into the kitchen to make dinner. For some reason, my TV was on PBS and I could hear Mr. Rogers talking from the other room. Despite paying only half an ear’s worth of attention, I suddenly realized what it was that earned the undying love of kids like my sister: Mr. Rogers made you feel like someone gave a damn about you. He said you were special. He did NOT, as the jackasses at Fox News and the Wall Street Journal claimed in hideous failure-blaming articles, promise you success or glory. He just told you that, no matter what you looked like, how able you were or how much money you had, that you had value.

I stood in my kitchen listening to this message, which I of course should have already known as an adult, and I started to cry. I tell you this because I had the same reaction at the end of “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” I sat in the critics’ screening room holding my notepad up to my face so that nobody would know I was sobbing. Now, if someone like me, whose childhood memories of Mr. Rogers involve rumored mass murder sprees, could have this reaction, you can only imagine what this film will do to you if you’ve always loved this man. Bring Kleenex. Lots of it.