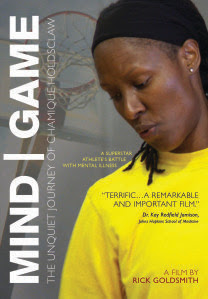

Mind/Game

56 Minutes | Blu-Ray

Matt Fagerholm

Some athletes are so thrilling to behold in action that they not only earn the admiration of typical sports aficionados, they seduce the world. Any Chicagoan who grew up in the ’90s can recall idolizing Michael Jordan when he led the Chicago Bulls to six championship victories. During the years of Jordan’s second “three-peat” with the Bulls, a college basketball player named Chamique Holdsclaw was making history as well. Her three championships at the University of Tennessee caused some commentators to predict that she could become the next Michael Jordan. Holdsclaw was such an unstoppable force on the court that she inspired fans of rival teams to cheer her on as she made basket after basket with seemingly effortless grace. It wasn’t long until Jordan found himself in a commercial on a golf course where he was asked by a caddie if he’d like to “Be Like ‘Mique.’

There’s no question the archival footage of Holdsclaw’s glory days are one of the chief highlights in Rick Goldsmith’s touching documentary, “Mind/Game,” yet the film is about a much deeper triumph. Something beyond her natural drive and ambition was fueling Holdsclaw’s momentum in these games, and it took a decade for her condition to be properly diagnosed. Bipolar disorder carries with it a stigma that has been intensified by sensationalistic thrillers such as Adrian Lyne’s “Fatal Attraction,” which its own star, Glenn Close, has credited with contributing to the public’s misunderstanding of mental illness.

Only recently has cinema presented audiences with far more humanistic portrayals of people with bipolar, particularly Valerie Weiss’ “A Light Beneath Their Feet” and Paul Dalio’s “Touched with Fire.” Both films meticulously portray the bursts of energy caused by an afflicted person’s symptoms and how difficult they are to bid adieu. Would Holdsclaw have reached the success she did if she had been medicated? Perhaps not, but there’s no denying that her greatness comes first and foremost from the strength of her character.

From an early age, Holdsclaw was tasked with much more than a person her age is often required to handle. Her mother’s drinking and her father’s undiagnosed schizophrenia forced her to be an adult when she was still a child. Her self-sufficiency proved to be an asset, as did the frustration she channeled into her performances in each game. Basketball became her coping mechanism, but it could only take her so far before the inevitable burn-out. Though she never became the “future of the WNBA” as the hype machine had predicted, Holdsclaw will leave an even more transformative impact on the sport through the power of her voice.

Goldsmith has a penchant for exploring the lives of those who break the mold, having co-directed the acclaimed 2009 documentary, “The Most Dangerous Man in America,” about whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg. Speaking out about one’s own mental illness as a female athlete of color is fraught with risks, and the strongest moments in Goldsmith’s film occur when he hones in on the insights Holdsclaw shares with others, whether she’s delivering a speech or teaching youngsters. An entire film could be built around Holdsclaw’s line about how minority communities refuse to accept the issue of mental health because they lack the resources to deal with it. “Praying it away” will do little more than lead one down the thorny path of denial.

By confronting her own issues and opening up about them, Holdsclaw’s heroism transcends the boundaries of sports. Her advocacy stands as a counterpoint to the secrecy so well-observed in Peter Landesman’s under-appreciated “Concussion,” where profit is repeatedly prioritized over the health of players, even after so many have succumbed to brain damage. “Mind/Game” clocks in just under an hour, though it leaves one wanting to see a more fully fleshed-out portrait of Holdsclaw. Still, it is a testament to Goldsmith’s editing that the picture doesn’t come off as a hagiography by gliding superficially through her challenges.

I especially liked the footage of Pat Summitt, the late, great coach at the University of Tennessee, who guided Holdsclaw through her early stumbles with a fiery authority that kept the already-lauded player on her toes. The film also pulls no punches in depicting the lows endured by Holdsclaw, following a series of personal tragedies. A suicide attempt or an arrest warrant would normally lead one’s life off the rails, but she continuously comes back all the stronger, while keeping her dignity intact. Not easily prone to crying, Holdsclaw’s voice momentarily cracks while speaking about her friendship with Asia Lampley, a bodybuilder who has also struggled with bipolar disorder. She’s the sort of ally that the basketball star may never have found had she not been brave enough to open up.

With its superb score by Miriam Cutler and narration by Glenn Close (a classy move, no doubt), “Mind/Game” is an inspiring portrait of an extraordinary female warrior. The open-ended quality of the film’s ending is entirely appropriate since Ms. Holdsclaw’s story is far from over. I cannot wait for the sequel.