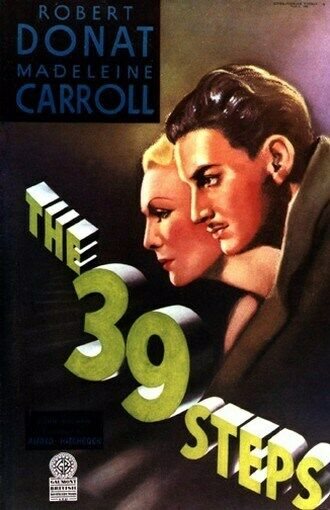

The 39 Steps

Rewatching Hitchcock’s “The 39 Steps”

By Michael Sragow

This review is courtesy of the New Yorker

“It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that all contemporary escapist entertainment begins with ‘The 39 Steps,’ ” Robert Towne, the screenwriter of “Chinatown,” once remarked of the 1935 Alfred Hitchcock thriller, which has just been rereleased by Criterion.

Hitchcock, drawing on characters and situations created by John Buchan (an action novelist he adored), concocted a classic movie-thriller recipe. He cast an innocent, amiable adventurer into espionage’s gale-tossed seas. Then he allowed this hero to sink so low that, to the public, he appears to be guilty of murder or even treason—until he rescues his good name and the security of his nation just before he’s due to fall for the third time. In this case, the reluctant hero is Richard Hannay (Robert Donat), a Canadian staying in London when agents of an espionage organization kill a glamorous spy (Lucie Mannheim) in his bachelor flat. Hannay goes on the lam to Scotland, where he searches for the spy network’s chief while eluding police who suspect him of the murder.

The story, at least in general outline, has been remade at least thirty-nine times. Hitchcock himself redid it most spectacularly in “North By Northwest.” (Robert Donat being tracked by an autogiro anticipated Cary Grant being attacked by a crop duster.) Hitchcock, ever the popular entertainer, saw how well this formula hurls audiences along with beleaguered heroes into a persecution-and-redemption fantasy, as enemy agents and police alike tail them across hill and dale and circle above them in the sky. It doesn’t give anyone the time to think, Oh, this is so much paranoia. And it allows a witty director like Hitchcock to rouse patriotic feelings without the jingoism that would jangle wised-up viewers.

But in “The 39 Steps,” Hitchcock’s most original invention is erotic. When Hannay makes his getaway from London on the Flying Scotsman, he startles a bespectacled blonde (Madeleine Carroll) in a train compartment, forcing a kiss on her to fool the cops in the train’s corridor. (Carroll, by the way, is the first of Hitchcock’s great cool beauties; when she drops her spectacles the effect is as electric as Dorothy Malone taking off her glasses in “The Big Sleep.”) Hannay expects her to believe in his innocence, as though she could have tasted his honesty. But he bets wrong. And in Hitchcock’s masterstroke, Hannay ends up handcuffed to this doubting, icy blonde and dependent on her for his freedom. Their oddest of odd-couple courtships is like an erotic version of tough love: the cuffs force them to get to know each other and test their mettle.

After watching the film again, and thinking how up-to-date and fresh it was, I called up Towne to ask him to elaborate on calling it the source of contemporary escapism. I caught him right before he was about to leave for London, where he’ll be researching a script on the Battle of Britain.

“I think it’s interesting,” he said, “Because most ‘pure’ movie thrillers, especially when you think of Hitchcock, are either fantasies fulfilled or anxieties purged. ‘The 39 Steps’ is one of the few, if not the only one, that does both at the same time. He puts you into this paranoid fantasy of being accused of murder and being shackled to a beautiful girl—of escaping from all kinds of harm, and at the same time trying to save your country, really. A Hitchcock film like ‘Psycho’ is strictly an anxiety purge. ‘The 39 Steps’ gives you that and the fantasy fulfilled. It’s kind of a neat trick, really.”

Back in 2000, Towne wrote his own version of “The 39 Steps.” In Hitchcock’s version, Hannay swiftly becomes notorious after the press reports the murder in his flat. In Towne’s script, “Rick” Hannay is already a celebrity. “Think a movie star who’s also disreputable: think Mel Gibson. I had the murder happen while he’s promoting a movie in Australia. So he’s a celebrity with a very bad public reputation, and he gets involved in the exact same way as in the old movie.” It’s a clever turn of the screw: the posters for the star’s new movie might as well be wanted posters. And when this Hannay first hears of “the thirty-nine steps,” he thinks it’s a drug rehab program.

Towne hoped that Rick Hannay’s rambles in the outback would conjure the same shrewd-yet-gallant, rough-and-ready spirit that Hitchcock found with Donat’s Richard Hannay in the Scottish moors. And there was talk of getting Towne to mount it in 2006, but he now says that it won’t be happening. As ample consolation, we still have “The 39 Steps” of 1935, an evergreen film that fulfills the writer John Buchan’s own definition of romantic adventure: “That which effects the mind with a sense of wonder—the surprises of life, fights against odds, the weak confounding the strong, beauty and courage flowering in unlikely places.”