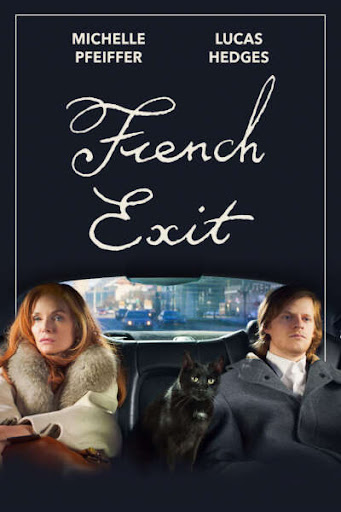

French Exit

Review by Christy Lemire

Her full-length, fur-trimmed wool coat is a suit of armor, the chicest of shields against both the cold and the cold stares of judgmental Manhattan society. Her ever-present cigarette is her sword, punctuating the many brittle witticisms that flit from her pillowy lips.

As broke socialite Frances Price in “French Exit,” Michelle Pfeiffer digs into one of her juiciest roles yet, one that plays on her impossible beauty as well as her capacity for lacerating detachment. Director Azazel Jacobs’ film, based on the novel by Patrick deWitt (who also wrote the screenplay), may be a low-key, melancholy farce, but it’s a showcase for the veteran star’s vibrancy. Even when the film as a whole grows a little ungainly, as it fills up with supporting characters who feel more like one-note ideas than actual people, Pfeiffer’s steely presence anchors the proceedings. The fact that Frances eventually allows her flawless veneer to crack a bit, revealing buried vulnerability, only makes her more compelling.

Jacobs and deWitt previously collaborated on the 2011 film “Terri,” a dry comedy with a tender heart about a bullied teen. Here, the tone is more arch, the language more stylized, and viewers may find that self-consciousness off-putting. “French Exit” exists within one of my favorite film subgenres—it’s a Sad, Rich, White People movie—but the characters are aware of their sorry state and eager to comment upon it wryly. As Frances’ future looks particularly bleak at one point, she remarks to her best and only friend, Joan (a lovely Susan Coyne), that she knows she’s a cliché, and she’s fine with that because it somehow makes her timeless. “French Exit” takes place in the present day, but its characters seem frozen in time a few decades in the past, with their use of pay phones and postcards to make awkward fumblings toward human connection. An eccentric, literary version of New York provides a strong vibe here, even when the characters pack up for France per the title.

Restless impulse drives the film from the start, as we see Frances plucking her teenage son, Malcolm, from his leafy boarding school unannounced. “What do you wanna do?” she asks with a conspiratorial gleam in her eye and just the slightest smirk. “You wanna come away with me?” We’re immediately hooked by her playfulness as well as her indifference to what others think. Fast forward several years, and Malcolm (an intentionally bland Lucas Hedges) is now a meandering twentysomething who’s secretly engaged to this longtime girlfriend (Imogen Poots). Frances, having been widowed a while now, is coming to the harsh realization that she’s blown through the family’s vast fortune. “We’re insolvent,” she informs her son, managing to stretch that word out to four syllables as she sips wine and sharpens knives alone in the darkened kitchen. She’s so broke, her $600 check to pay the housekeeper bounces.

But Frances lucks into an escape from both the misery and scrutiny she’s suffering when Joan offers to let her and Malcolm stay in her empty apartment in Paris. “To get out of New York is the thing, honey,” she assures Frances over Bloody Marys at a tony restaurant. And so, following Steven Soderbergh’s cruise comedy “Let Them All Talk,” we have yet another movie in which Hedges plays an aimless young man accompanying an older female relative on a transatlantic journey. Also along for the trip is the family’s black cat, Small Frank, who has an intensity in his green-eyed stare that suggests he understands keenly what’s going on around him. (And the great Tracy Letts, co-star of Jacobs’ “The Lovers” who eventually provides the resonant voice of Small Frank, goes woefully underused. This could have been wall-to-wall talking cat and I would have been totally fine with that; besides, the surreal nature of such a notion would fit just fine with the film’s increasingly screwball sensibility.)

Once Frances and Malcolm arrive in Paris and settle into the same sort of sad routine they had back home, they find their lives upended by a widowed expat who goes by Madame Reynard, who invites them for dinner even though they’ve never met. Valerie Mahaffey is a complete delight in the role; she changes everything about the film with her sweetly bubbly personality and her earnest efforts at friendship. In a movie full of characters who put on a façade and play a role to fend off genuine feelings, Madame Reynard is a breath of fresh air with her warm humanity and emotional truth. “I’m … lonely,” she explains when Frances coldly asks why she invited them there, and her honesty is heartbreaking.

But as the Paris flat grows crowded with the arrival of wacky supporting characters, “French Exit” loses its way. Small Frank also gets lost, scurrying away from the apartment and slinking through the streets alone. Not only do we have a fortune teller from the cruise ship who experienced a psychic connection with the cat (Danielle Macdonald), we also have the private investigator Frances hires to find him (Isaach De Bankole). Eventually, Susan comes back into Malcolm’s life, with her handsome and vapid new boyfriend in tow (Daniel di Tomasso). And ultimately Joan returns to check on her friend, unaware that her apartment has become a makeshift bed and breakfast. There are so many people crammed in here that there’s no room for any of them to become fleshed out, and they detract from the folks we’d come to care about.

Occasional glimmers of grace do surface, though. Mahaffey remains a charmer. The bond between Pfeiffer and Coyne feels deep and true. The costume design from Jane Petrie creates a timeless elegance. And Pfeiffer’s performance only becomes richer as her character reveals the kindness that’s been buried within her cool, stylish persona all this time.