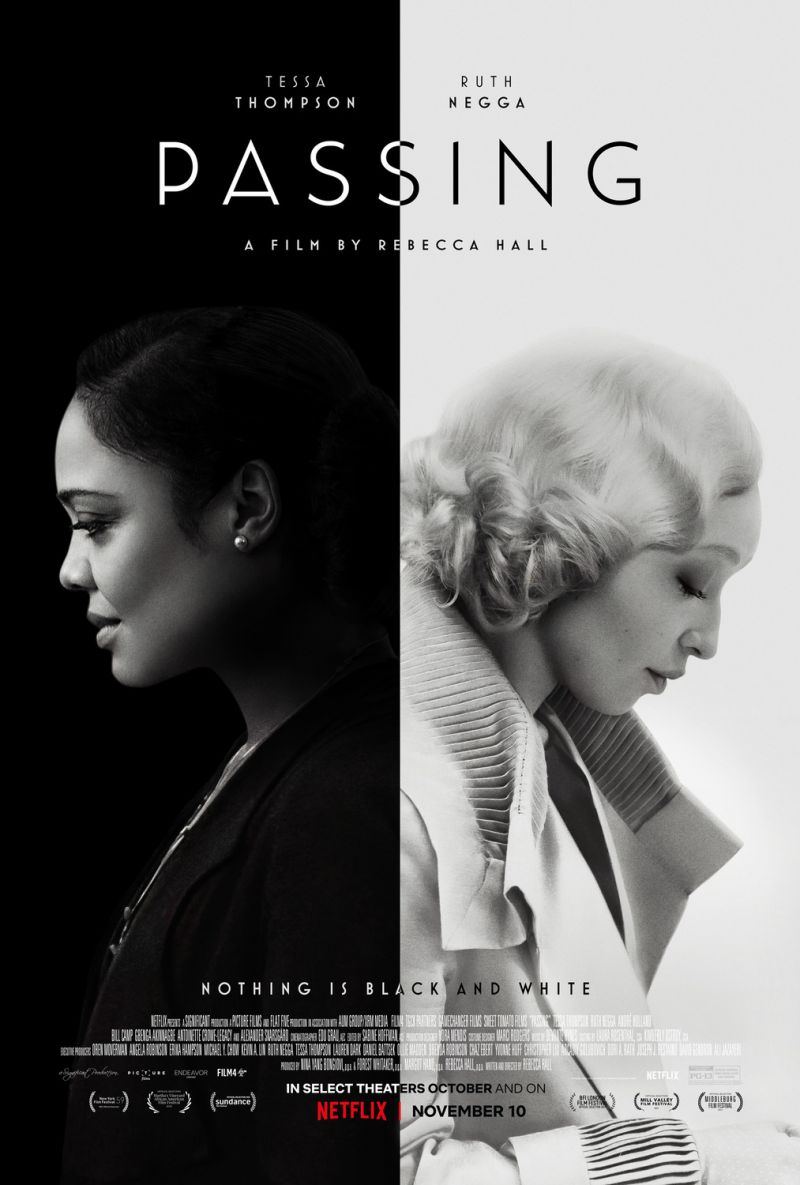

Passing

Odie Henderson

As I watched writer/director Rebecca Hall’s adaption of Nella Larsen’s 1929 novella, Passing, I couldn’t stop thinking about the story in “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” where “a colored man” named Eliza Cottor sold his soul to the Devil. The sale made him impervious to consequence, not just for big crimes like committing a murder, but also for small, self-assured gestures that would have certainly gotten his “uppity” ass lynched. August Wilson’s metaphorical tangent struck me as ironic because, as I wrote in my review, “it seems the only way for a Black man to enjoy the same freedom as his White counterpart in the 1920s is to broker a deal with Beelzebub.” But I understood why Eliza Cottor made that arrangement. He surrendered his soul, but not his identity. In the former scenario, Hell awaits you when you die; in the latter scenario, chosen by this film’s free spirited Clare (Ruth Negga), Hell can be visited by the living.

Clare is a Black woman passing for White. She’s convincing enough to fool a lot of people, including John (Alexander Skarsgård), her vile, racist husband. Before we meet Clare, we follow her old high school classmate, Irene (Tessa Thompson) who, on this particular day, has decided to try her hand at fooling the masses. She nervously enters a White dining establishment and takes a seat. Hall’s camera, emboldened by Eduard Grau’s stunning black-and-white cinematography, casts a lengthy gaze at Irene’s face under the hat she’s pulled down low enough to arouse suspicion. This beautiful close-up immediately sent my brain to its Blackest depths. “Gurl, there’s no way you’re fooling anybody!” I thought. “Not with that nose and mouth!” I started to think about Billy Wilder’s choice to shoot “Some Like It Hot” in black and white so as to mute the fact that Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis are some very unconvincing women.

My temporary disbelief was suspended by a major jolt of reality: Unlike the waiters and patrons surrounding Irene, I know what to look for when it comes to recognizing my own people. Some of these “how to notice your Negro” tips I’ve read by Jim Crow-loving idiots weren’t even close to accurate. So I was gripped by suspense during this scene. Hall’s camera takes Irene’s point of view, darting around and quickly noticing Clare. Then the viewfinder rests on her for an uncomfortable amount of time. We sense a possible familiarity between the two, but the uncertainty of the moment hangs in the air.

Clare initiates their meeting, and the two share old memories and their current secret pastime. She’s in New York City as her husband conducts business. Clare peppers the conversation with news and gossip from their hometown. During the chat, Irene mentions her husband, Brian (a superbly understated André Holland) and the two sons she shares a house with in Harlem. Going one better than a verbal description, John is formally introduced when he interrupts the two friends’ reunion. Thinking Irene is White, and someone who agrees with his worldview, John drops his guard the way people like him always do when they think they’re amongst friends.

What follows is one of Thompson’s best scenes in the film. The horrific dialogue on the surface may distract from what she’s doing, so focus on how swiftly she manages to keep herself in check as her body language almost betrays her. John mentions how much he hates Black people, which we expect. Then he points out that Clare also hates them, but has “been getting darker and darker every year we’ve been together.” This worrisome feature earns her the nickname “Nig,” which John sees as both a term of mockery and endearment. The second syllable of her nickname is implied, and you know damn well it’s with a hard R. Thompson and Negga play this scene as a duet of dueling but equally subtle reactions. For a moment, it appears Irene may out Clare to her boorish man, and the tension Hall and her actors generate is as white-knuckle as any action chase scene.

Though Irene wants nothing to do with Clare after this, she’s cordial when Clare shows up at her doorstep unannounced. Their friendship is rekindled, partially out of curiosity and perhaps more than a bit out of guilt. Without sacrificing her Blackness, Irene lives a rather bougie life in her brownstone. But she’s practically a prude compared to the flapper-like exuberance Clare reveals once she’s able to sneak back to the cookout. During these social gatherings for the Negro Welfare League, Clare is a constant source of fascination, from the Black men who fawn over her light-skinned beauty to a snooty White writer, Hugh (Bill Camp), who’s supposed to be an ally but comes off as someone observing Black folks as if he were watching a National Geographic special. When Hugh asks why Clare would go to a dance in Harlem after she’s technically “escaped” her Black existence, Irene responds that she’s there “for the same reason you are. To see Negroes.”

“To see Negroes.” It’s a good line, a well-observed comeback that has sharper teeth than its humorous delivery implies. One is inclined to meditate on how much Clare longs to be amongst her people again, and how her temporary happiness throws Irene’s disposition off-kilter. Things get worse when it appears Brian may have more than a friendly interest in this enigma who wants to have her Black and Whiteness too. And Clare is an enigma, which was my initial problem with “Passing.” As good as Negga is, she’s mostly left to our own devices of interpretation. This bothered me until I realized that Irene is our stand-in. We know as much as she does. As she tries to figure Clare out, and reconcile her own feelings, we’re doing the same.

Hall, Grau, editor Sabine Hoffman, and composer Devonté Hynes do an excellent job of casting a hypnotic spell on the audience. This is a deliberately paced film with enveloping moods that feel like symphony movements. There’s heavy material here, but “Passing” doesn’t belabor its points. When Brian rightfully tries to warn his sons about the racist trouble they’ll face in the world, Irene argues that they should have some innocence in their youth. We understand both arguments even though we know one of them is very, very naïve. The entire film exists in this perpetual state of a deceptively gentle push and pull. It’s a masterful balance of tone. And even though we anticipate the ending, it comes with a surprising amount of empathy and sadness, two things that were always subtly present during the runtime.

“Passing” put me in a very thoughtful mode of allusion and pattern-gathering. On a parallel track, my mind went to other features, from Douglas Sirk’s “Imitation of Life,” my third favorite movie of all time, to “Watermelon Man,” which is a directly opposite story. The one connection that, like “Ma Rainey,” I couldn’t shake was, of all things, Spike Lee's “BlacKkKlansman.” Adam Driver’s character has to pass for a White character played by a very Black John David Washington, and in doing so, he navigates an anti-Semitic and hateful world that would kill him if his Jewishness were revealed. He has it a lot easier than Clare does here, but Lee allows us to navigate his torment. I imagined a similar agony befell Clare in those moments when we don’t see her, when she’s alone with her demons.

My pensive mood eventually led me to my old church-going days, and Matthew 16:26, which says “For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul? Or what shall a man give in exchange for his soul?” That kind of sums things up here, but to be honest, I wonder just how little worry I’d have about my soul if I got what I wanted in this life. I don’t think I could give up who I was, though. Like I said, that would be some kind of living Hell.